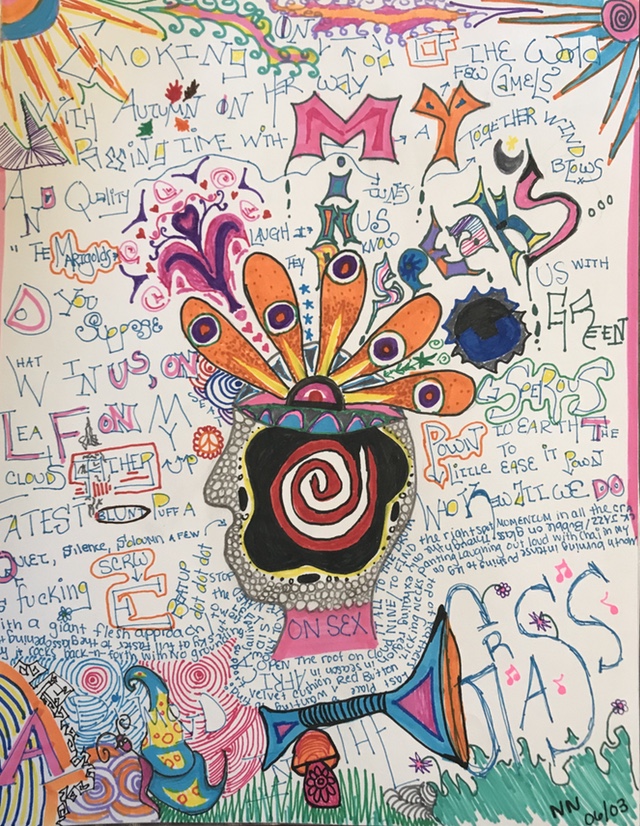

Our bravest contributors have shared with us some of their more earnest efforts from the misty past. Scary Bush should not be reviewed while in the process of drinking liquids, and the reader assumes all risk.

Untitled

Nikoletta Nousiopoulos

Untitled

Amanda Pampuro

29. Verbs

Ryan Clark

29. Verbs 1

Thief eye

forms

of her bees,

you see.2

The ape rope riot:

Ox eye Larry

of her bees.3

This sting wish:

beat we in

lion lay,

sight hand

see tree see

and ray I see.4

See cue in sea

of her bees.

Tenses a cure:

a tea lie,5

you see.

Act I of

of oh I see

and pass I of

of oh I see:

a prop riot tea lie.6

See.

Elect the a:

prop riot tea mood.7

_______________

1 Lunsford, Andrea. The Everyday Writer.

2 29a The five forms of verbs.

3 29b Use the appropriate auxiliary verbs.

4 29d Distinguish between lie and lay, sit and set, rise and raise.

5 29f Sequence verb tenses accurately.

6 29g Use active voice and passive voice appropriately.

7 29h Select the appropriate mood.

On Top

Jay Halsey

Beware of Virgin

Kelly Gangeness

Beware of virgin

Crawling in your bed

Inside your head

Run like plague!

The virgin is coming, the virgin is coming!

AHHHHH!

In purity she has preached

A succubus, a leech!

The virgin is coming, the virgin is coming!

Under her

We die wrapped with sheets

The monster,

The beast!

Untitled

Suzanne O'Connell

Fiscus Apostina

Finley J. MacDonald

Madame Cracey stretches for cigarettes and bumps the wine flute, which bursts against the floor. On a blue wave, fragments twirl and slide. Shaved cats gallop along two sets of windows. Among the potted trees at the edge of the floor space, they peek and stalk while in the kitchen cracks Berthold’s Utteringrish ditty. And in the front yard, an imperial pigeon with gray wings jerks off a fig: fiscus apostina. A number of species, including the Harlequin Fruit Dove and Cresson’s Crowned Pigeon favor that fruit, and yellow seeds are scattered about the soil. A hand comes down from Madame’s face. Her shoulders are stiff, lips parted, eyes fixed.

“Mais pas grave,” says Mr. Cracey.

“Motherpiss.”

“We have other glasses.”

“Don’t apprise me of our glasses. I order them.”

“Why, you are allowed to break a glass.”

That’s not the point.

“What is the point?”

“The point is.”

“Yes?”

“The point is I was obliged to wait three months for that glass. The point is, as everyone knows, fifty-dolerais stemware should be placed at eleven o’clock. Not at five o’clock. There is a reason for that.”

At the head of her reflection Berthold fills the doorway, permanent smile deepening the puckerwork at the corners of her eyes. Across the glossy slab, she staggers like a golem, the bottle a weapon in gnarled hands, her foot dragging, apron slightly soiled. Across the floor of the Cracey dining hall she staggers, mindful of her brittle bones, a paragon of longevity, an embattled clipper outdistancing a cape of dead: lovers, husbands, comrades, enemies, children. She staggers free of care toward a grave that cannot be far off.

“Thirty-eight, sir.”

“Open it. Then fetch a broom. I’m afraid that we have a catastrophe.”

“Of course, Mr. Cracey.”

“And fetch Madame a glass.”

“Of course.”

Berthold clunks the bottle bottom first on the table, and Madame winces as her deformed hands wrench the corkscrew. The music machine exudes a monotonic dirge, and the emotodome covers Berthold in beige light. The bottle pops. Berthold drops the corkscrew into her apron and bears the trembling cork beside Cracey’s dessert fork. She treks back across the blue floor, and a cat, lashing its tail, follows her into the kitchen. Madame lights a cigarette.

“I cannot bear them any longer. Relics of your childhood.”

“We can’t dismiss our entire household.”

“Really, I cannot.”

“They have been with us since—”

“I haven’t the energy to keep tabs on your menagerie of crones.”

“No one is asking you to.”

“Meanwhile, our guests come trudging to the door on foot?”

“I enjoyed the walk, Madame Cracey.”

“I should have checked the handhelds.”

“This all has to change. I cannot bear it. My health is at risk.”

Beamed onto Mr. Cracey’s face, which is sinking into his palm (I recall a man’s face crushed into his hand, just so, before us children) the flush of the emotodome has become a gray-yellow pall. Yellow of hysteria. Wild venom of deranged justice. Gray of defeat. Of crumbling, helpless masculinity . . ..

Or haze of blame, acrid and unmitigated, eroding the image of a man who longed for love like a child, who could not divest himself of carnal vitiation, who gave into it like a bed wetter, who purported falsely to be our exemplar of faith and stoicism, who was all Achilles heel and weak spine and craving, ready to sacrifice us all, every starch-shirted child frozen behind his plate at a glass table within a trembling, tipping house of glass—for another her.

Berthold, again, broom in one fist, tin dust pan in another, plugs our way across the glowing space, ankles wreathed in cats. She brings a smile that dawned across her face with a second childhood. Imbecilic, proud of accoutrements, she comes on, an emissary of the blithe menagerie of crones who don’t bother about roadcarts and handhelds. Berthold who remains like a camphor tree in the forest with the forms of almost everyone she knew fallen around her. She cracks to one knee and brings in glass and bluewine with jerks of the hand broom and tells us her thoughts, apropos of nothing, on reincarnation.

“Used ta tell Mr. Cracey when he was a bean. Don’t matter how big your house is or how much money ya got. Do the best ya know how this time around. Next time maybe you are going to be a snake. Sliding on your belly, ha-ha, boys lobbing rocks in your direction. Next time maybe you are going to be some Zipango with two heads and two mouths ta feed. Now, how would that be? Both heads saying, feed me. No, feed me. I prefer rice. I prefer porridge.”

“I don’t quite agree, Berthold,” says Mr. Cracey.

His chair screeches, and he leans over the table, the ivory buttons of his sleeve shining as he empties his glass, dribbling wine over the suckling pig.

“Two heads are not such a burden to the monster who sports them. They burden the rest of us. Especially those charged with care and feeding. Two heads might actually be an advantage. A man with two heads can never be lonely. You could devote one head to philosophy, for example, one to aesthetics. One to dalliance, one to drudgery. If I had an extra head, I would devote it entirely to the memorization of texts.”

He picks up the half-full bottle of bluewine by the neck and pours that also over the back of the piglet.

“What on earth are you doing?” says Madame Cracey.

“I am pouring out a weak vintage.”

“Over our meal?”

“Consider it an offering—”

“I consider it an outrage.”

“To the gods who punish hubris. Studebaker, which are those?”

Bluewine knocks the slice of tomato from the eye and runs between the squares cut in the flesh, adding to a greasy pool in the platter.

“All of them, I suspect.”